Now coming to Miami’s Wynwood district: condos

By Andres Viglucci

In the evolution that has taken Wynwood from industrial wasteland to hipster mecca in the seeming blink of an eye, the artists who came looking for cheap studio space were just the first step out of the muck.

After them, in an accelerating process of adaptation, came the art galleries, the eye-grabbing graffiti murals, the artisanal coffee, the art-walk party mobs, and the conversion of dingy warehouses into stylish spaces for bars, restaurants and loft-like offices for the creative set.

Now there’s something else rising in Wynwood.

Apartments and — gasp! — condos.

For the first time since Wynwood became Miami’s hippest ’hood, developers have plans to erect a half-dozen new buildings in the district. Proponents say the building plans, which mix residential units with work spaces and ground-floor shops, would add the last critical missing link in the rapidly diversifying neighborhood ecosystem: People who actually live there.

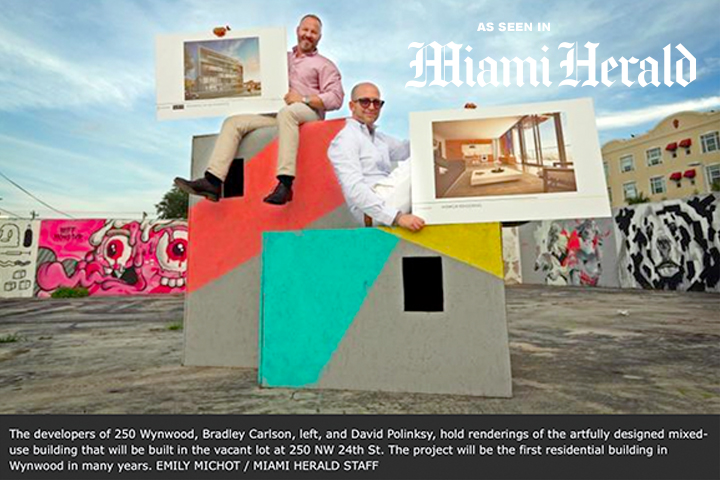

“I think it will change the perception of Wynwood,” said David Polinsky, whose 250 Wynwood, an 11-unit condo with ground-floor retail and terrace overhangs that will be decorated with curated graffiti, is set to break ground in the next few weeks.

“There is so much good will and enthusiasm about the neighborhood, but there are basically zero options for housing,” he said. “It can be a great place for young creative people to live and work. You can’t really think of another neighborhood where that’s going on in Miami.’’

Across the street from Polinsky’s property, several small warehouses have come down to make way for the eight-story Wynwood Central, which will combine 69 live-work rental apartments, a 420-space parking garage and three floors of retail and commercial space.

A few blocks away, on North Miami Avenue, New York developer Sonny Bazbaz is seeking zoning approval for a 12-story apartment and extended-stay hotel complex. On a vacant lot north of the famed Wynwood Walls, Goldman Properties, which helped launch the Wynwood renaissance, has won rezoning for a mixed-use building that could include 55 dwellings, a 100-room hotel and an event space described as “industrial chic.”

The Wynwood story seems to be following a well-worn script: artists and urban pioneers reclaim a neglected neighborhood, only to be displaced by rising prices and monied gentrifiers, erasing the very character that made it cool in the first place.

So there goes the neighborhood, right?

Actually, not so fast.

In what might be a radical departure for Miami, Wynwood developers say they are eschewing the usual hot-neighborhood development model of maximum exploitation with minimum care.

They have formally banded together with local entrepreneurs and new and longtime Wynwood property owners to devise a strategy that would foster affordable residential development while preserving Wynwood’s unique flavor and the pedestrian-friendly scale of its streets.

“We’re trying to create for the first time in Miami a very comprehensive approach to how zoning will guide development of a neighborhood,’’ said Joe Furst, managing director for Wynwood at Goldman Properties and chairman of the new Wynwood Business Improvement District, which is overseeing the planning effort. “We all love what we’ve created in the neighborhood, and we’re trying to do it right.’’

Plenty of space

The effort aims to remedy big drawbacks boosters say have held back Wynwood’s emergence as a full-fledged neighborhood: It contains little housing and few residents. Its warehouses are unsuited for residential conversion. And the district’s predominantly light-industrial zoning sharply limits housing density.

The Wynwood industrial district, between I-95 and the FEC tracks to the east and from 20th to 29th streets, has only about eight blocks of modest duplexes and small apartment buildings, plus a smattering of detached homes and a large homeless shelter, the Miami Rescue Mission. Two newer residential buildings, the rental Cynergi lofts and Wynwood pioneer David Lombardi’s Wynwood Lofts 36-unit condo, predate the current boom.

Within that defined zone, developers and property owners say, there’s plenty of space for new residential development; 60 percent of the district consists of vacant land, a BID survey found. But there are legal hurdles. The light-industrial zoning restricts housing to a live/work arrangement that requires residential floorspace to be clearly divided between either use.

Developers say zoning restrictions in effect require relatively large residential units, not the smaller, more affordable housing that would appeal to the young creative types who would make up the likely Wynwood residential market.

With the exception of Wynwood Central, which has large units up to 2,500 square feet, all the other projects have won or are seeking rezonings.

The BID, which represents the area’s 200 property owners, wants to see zoning restrictions loosened. But its leaders worry that a big wave of development could encourage warehouse demolition and overwhelm the neighborhood’s funky street ambiance.

The last thing they want, BID leaders and property owners like Lombardi and others insist, is to bring in intense high-rise development of the kind that has overtaken hot redevelopment zones like Brickell Village or Edgewater.

The BID, a city-approved group funded through a special property assessment, has commissioned planner Juan Mullerat of Miami firm PlusUrbia to draw up a master plan and zoning to guide Wynwood’s redevelopment.

The plan would continue to restrict new construction to eight stories in most of the district while promulgating a design aesthetic to mesh with the warehouses and the low-scale street grid. It calls for apartments upstairs and active storefronts on the sidewalk to promote pedestrian activity and capture the artists, designers, chefs and tech entrepreneurs already flocking to Wynwood.

To keep things affordable, BID leaders want to rezone most of the district, expanding housing density to 150 units per acre, from the current 36, to allow smaller units in modestly scaled buildings without obliterating the neighborhood. They also would like to see a parking minimum of 1.5 spaces per unit eased.

“This is what’s needed if we’re going to see Wynwood reach its potential as a living, working community with real creatives here eating, sleeping and collaborating 24 hours a day,” Lombardi said.

A careful balance

The city says it’s on board with the idea, but is awaiting a final BID draft. City planners warn that the fixes must strike a careful balance if its proponents wish to preserve Wynwood’s character.

“I’ve been hearing a lot about preserving the soul of Wynwood — it’s easy to latch on to that,’’ said Cesar Garcia-Pons, the city’s deputy planning director. “But the outcome could be the entirety of Wynwood being 12-story residential towers. Then it’s not Wynwood anymore.”

BID leaders seem acutely aware of the pitfalls. At a recent meeting, members debated how to encourage preservation of the warehouses and graffiti that have come to define Wynwood.

“If you don’t have a mechanism to protect the warehouses, before you know it, you have just another neighborhood,” said Oren Cohen, vice president of Mana Wynwood, which refurbished the old free-trade zone complex for use as video and sound and video stages. “There has to be a way of keeping the feel.’’

But rules requiring preservation of warehouses may not be feasible and could stifle Wynwood’s serendipitous evolution, Mullerat replied.

“To maintain the industrial feel is important, but these warehouses don’t necessarily need to remain,” he said. “One of the beauties of Wynwood is that it was accidental. That soul has sort of created itself. ’’

In the absence of clear rules or established templates, the developers of 250 Wynwood and Wynwood Central say they have gone to great pains to make sure their designs are in sync with Wynwood.

Polinsky, who is on the BID’s board, says his small building serves as a demonstration project for the neighborhood — edgy enough to break the mold of Miami condos, but sympathetic to its artsy surroundings. His New York architects, D-form-A, set glass-fronted units behind a pattern of rectilinear interlocking terraces overlooking the street. Blank walls on the sides echo the basic concrete construction of its warehouse neighbors.

To incorporate street art, Polinsky hired hot gallerist Anthony Spinello to select artists who will apply geometric, graffiti-style murals to the undersides of the terrace overhangs. The art will be visible from the sidewalk and frame residents’ views, but not blanket the building, Polinsky said.

Wynwood Central developers Marc Kovens and Shawn Chemtov are forgoing graffiti. But they hired Bloom Miami, a branding and design firm, to work with architects DNB Design Group and ensure their new building is “accepted” by its hip Wynwood neighbors, Bloom partner Darin Held said. That meant interviewing Wynwood entrepreneurs and creative lights and incorporating simple industrial design elements like factory-like neon signage into the building.

“We’re not looking to just come in and make a lot of money,” said Wynwood Central leasing agent Lyle Chariff. “I think what we’re doing will be a catalyst and the footprint for what’s going to happen.’’

Still, as developers snap up land and warehouses, prices in Wynwood are rising fast. Lots are selling for up to $300 a square foot. Owners have sunk considerable money into converting warehouses into shops and offices — in high demand as Wynwood becomes a serious place to do business.

That’s a boon to some longtime property owners who suffered through lean years and can now sell for millions. But rising rents means some art galleries and studios have been forced out, and more likely will follow, Mullerat said.

“The gentrification has already happened,” Mullerat said. “The market has pushed land values to levels that are not sustainable for some of the existing businesses.’’

But BID leaders and some longtime Wynwood business and property owners say the changes are, on balance, all to the good.

“This was the kind of place that, at sundown, you would tell your employees, ‘Get in your car and go home,’” said BID board member Albert Garcia, whose family business, Mega Shoes, an international maker of women’s fashion footwear, has been based in Wynwood since his parents founded the company 40 years ago. “Fast forward to today, and people are walking the sidewalks all hours of the day and night.’’

But Garcia, chairman of the BID board, said it’s also important that the history and DNA of the neighborhood be preserved even as it changes.

“We’re not a high-end mall. We are not a row of bars and restaurants catering only to nightlife. And we’re not an assortment of galleries, either. It’s not going to become Doral. We’re not trying to become Design District Junior. Our path is a little different, and I think it’s the most authentic,’’ he said.

“It’s going to evolve, and that’s OK.”